Hidden order in quantum chaos: the pseudogap

29 Jan 2026

In a quantum simulator LMU and MPQ physicists reveal how subtle magnetic patterns shape one of the most puzzling states of matter - an important step towards understanding superconductivity.

29 Jan 2026

In a quantum simulator LMU and MPQ physicists reveal how subtle magnetic patterns shape one of the most puzzling states of matter - an important step towards understanding superconductivity.

Superconductivity – the ability to carry electricity without resistance – has driven decades of research. Yet, in many high-temperature superconductors, the transition to this state is not abrupt. Instead, the material first enters a curious intermediate regime known as the pseudogap. This mysterious phase of matter appears in certain strongly-correlated materials just above the temperature at which they become superconducting. In this phase electrons start behaving in unusual ways, and fewer electronic states are available for conduction. Understanding the pseudogap is widely considered essential for unravelling the mechanisms behind superconductivity and designing materials with improved properties.

For the first time, we were able to demonstrate that microscopic arrangements of particles exhibit universal behaviour as soon as they enter the pseudogap phase. This behaviour was both surprising and unexpected.Immanuel Bloch

An international team of scientists led by LMU physicist Immanuel Bloch, member of the MCQST cluster of excellence, has uncovered a new link between magnetism and the so-called pseudogap. Using an ultracold atom quantum simulator, researchers discovered a universal pattern in how magnetic correlations evolve as the system cools – an important step towards understanding unconventional superconductivity. 'For the first time, we were able to demonstrate that microscopic arrangements of particles exhibit universal behaviour as soon as they enter the pseudogap phase,' explains Immanuel Bloch. 'This behaviour was both surprising and unexpected.' The findings were published in science magazine PNAS.

In typical, undoped systems, electrons arrange themselves in an orderly magnetic pattern known as antiferromagnetism, in which neighbouring electron spins point in opposite directions – like dancers following a precise left-right-rhythm. But when electrons are removed, a process known as doping, this magnetic order becomes strongly disrupted. For a long time, researchers assumed that doping destroys long-range magnetic order entirely. The new study in PNAS, however, shows that at extremely low temperatures, a subtle form of organisation remains, hidden beneath the apparent disorder.

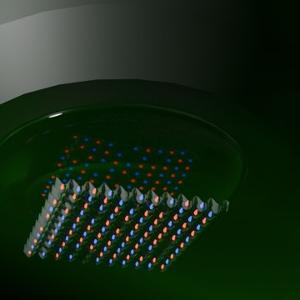

This device enables researchers to image atoms in high resolution and visualize both their spatial position and their magnetic correlations. | © Titus Franz, MPQ

To explore this behaviour, the research team turned to the Fermi-Hubbard model, a well-established theoretical framework that captures how electrons interact inside a solid. Rather than working with real materials, the team recreated the model using lithium atoms cooled to billionths of a degree above absolute zero. The atoms were arranged in a precisely controlled optical lattice made of laser light.

Such ultracold atom quantum simulators allow scientists to mimic complex materials under controlled conditions, something impossible in traditional solid-state experiments. Using a quantum gas microscope – a device capable of imaging individual atoms and their magnetic orientation – the research team took more than 35,000 high-resolution snapshots of individual atoms. These images revealed both the spatial positions and magnetic correlations of atoms across a wide range of temperatures and doping levels.

The results were striking: “Magnetic correlations follow a single universal pattern when plotted against a specific temperature scale,” explains lead author Thomas Chalopin from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics at Garching and member of the MCQST cluster of excellence. “And this scale is comparable to the pseudogap temperature, the point at which the pseudogap emerges”. In other words, the pseudogap is linked to the subtle magnetic patterns hidden behind the apparent chaos.

The study also revealed that electrons in this regime do not simply interact in pairs. Instead, they form complex, multi-particle correlated structures. Even a single dopant can disrupt magnetic order over a surprisingly large area. Unlike previous studies, which focused on correlations between two electrons at a time, the new study measured correlations involving up to five particles simultaneously – a level of detail achieved by only a handful of labs worldwide.

By revealing the hidden magnetic order in the pseudogap, we are uncovering one of the mechanisms that may ultimately be related to superconductivity.Thomas Chalopin

For theorists, these results provide a new benchmark for models of the pseudogap. More broadly speaking, the new findings bring scientists closer to understanding how high-temperature superconductivity emerges from the collective behaviour of interacting, “dancing” electrons. “By revealing the hidden magnetic order in the pseudogap, we are uncovering one of the mechanisms that may ultimately be related to superconductivity,” Chalopin explains.

The study also highlights the power of collaboration between experiment and theory. By combining detailed theoretical predictions with highly controlled quantum simulations, the researchers were able to identify patterns that would otherwise remain concealed.

The research is the product of an international collaboration, combining experimental and theoretical expertise. Future experiments aim to cool the system even further, search for new forms of order, and develop novel ways of observing quantum matter from fresh perspectives.

Thomas Chalopin, Petar Bojović, Si Wang, Titus Franz, Aritra Sinha, Zhenjiu Wang, Dominik Bourgund, Johannes Obermeyer, Fabian Grusdt, Annabelle Bohrdt, Lode Pollet, Alexander Wietek, Antoine Georges, Timon Hilker, Immanuel Bloch. Observation of emergent scaling of spin-charge correlations at the onset of the pseudogap, PNAS 2026.